When I decided to learn to draw I had no idea I was going to discover a world of boundary crossers and metaphor makers who value negative space and think symphonically. Drawing, I discovered, is more about perceiving relationships than making marks on paper.

Every quest starts somewhere and my quest to learn to draw began at the Los Angeles Academy of Figurative Art in Los Angeles. I dropped by one Saturday afternoon for a free drawing class. The instructor spoke to the class about the history of drawing before demonstrating several techniques. After the presentation a model stepped onto a small stage and disrobed under the spotlights.

I tried to maintain proportion and perceive relationships as I sketched, but the drawings did not look very good and I felt confused and disoriented. My quest had begun.

The instructor recommended a book entitled “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” by Betty Edwards. That evening I googled the title and discovered that a course with the same name was about to start at the Otis College of Art and Design on Lincoln Blvd.

The instructor for the course at Otis was Linda Jo Russell who appears in the acknowledgments of the book. The author thanks Linda Jo for her “unfaltering devotion to our efforts.” My quest was taking shape.

Linda Jo has been teaching people how to draw for over forty years. She has conducted classes and workshops in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The Otis College of Art and Design on Lincoln Blvd in Los Angeles is her home base.

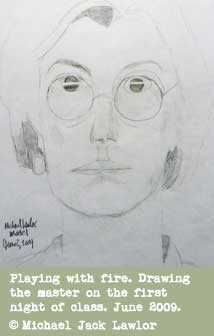

On the first night of class, without giving us any instruction, Linda Jo sat on a stool and told us to draw her portrait. The process of trying to draw Linda Jo’s portrait involved looking at her and feeling my arm lock as I shifted my gaze to the blank page in front of me. After awhile I managed to sketch a likeness, including an attempt to draw the light reflected in her glasses. When she saw my drawing, Linda Jo asked if her eyes really glared like that. Drawing people can go badly very fast when you don’t know what you are doing.

As the course progressed we engaged in drawing exercises that made us perceive contours and object edges. Linda Jo told us that people often confuse what they already know with what they see.

To curb the conflict between what is seen and what is known, and to bypass internalized symbol systems and predetermined ideas, we performed blind contour drawing exercises. Blind contour drawing involves drawing objects without looking at the paper. Learning to draw, I was beginning to discover, is really about learning to see, which is different from just looking.

“Drawing needs to be taught,” said Russell. “For the most part people need instruction to be able to draw.”

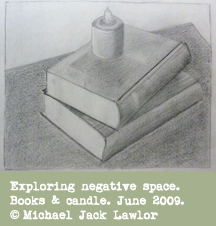

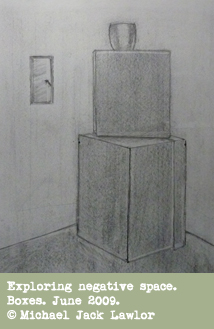

The struggle to bypass internalized symbol systems and predetermined ideas is often resolved when students discover the ability to perceive negative space. Negative space is the area around an object that shares an edge with the object. “Negative space is new learning for most people,” said Russell. “Drawing is easy if you can access negative space.”

In class we explored negative space by drawing chairs, boxes, vases, books and candles. “In the beginning when you look at negative space you get a strange feeling. After awhile the brain begins to cooperate and you feel more natural looking at it,” said Russell.

Once you get a feel for negative space you start to see it everywhere. Driving home after class I found myself observing negative space around cars on the freeway and between electrical wires and telephone poles on the street. Awareness of negative space revealed touches of previously unnoticed rhythm and beauty in the clutter of the urban environment.

Linda Jo encouraged us to listen to classical music when drawing because it often helps people bypass internalized symbols and perceive forms as they really are.

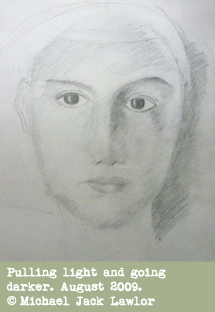

We learned to be mindful of measurements and landmarks when drawing a face. All landmarks in a drawing are related to the distance from eye level to the chin. The base of the nose and closing line of the mouth must be located in relation to this basic unit of measurement. Other important measurements include the distance from eye level to the top of the head and to the back of the ear. You start to see triangular relationships everywhere in a drawing when you work with these relationships.

Proportion is critical to the success of a drawing. The nose is at least as wide as the eyes are apart and the mouth is slightly larger. The base of the nose is more than a third but less than a half from eye level to the chin. The central axis of the face always runs through the third eye and the twin peaks of the lip, regardless of foreshortening. Break the width of the eyes into thirds.

Linda Jo introduced sighting techniques that make relationships between angles and proportions easier to see. We explored light-logic in the context of drawing highlight, reflected light, crest shadow and cast shadow.

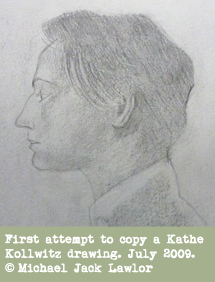

There seems to be moment during the process of drawing faces when an image comes to life and takes on the imaginative quality of a waking dream. I discovered this phenomenon one time when I was making a copy of a drawing executed in 1889 by Kathe Kollwitz entitled, “Self-Portrait in Profile, Facing Left, II.”

As I drew, I realized that the figure I was making did not look like the one I was trying to copy. I was agitated by what I perceived to be a failure to reproduce what was right in front of me.

I started scrubbing out lines and redrawing, checking back and forth between my drawing and the one I was trying to copy to see if things were synching up. When I drew in this state the drawing became worse.

After awhile I just allowed my own drawing to unfold. When I worked this way I discovered that I was deeply involved in the process of drawing, even though the image did not look like the one I had been trying to copy.

When I brought the drawings based on the Kathe Kollwitz piece to class Linda Jo asked me if they represented the same person. “Yes,” I replied they are both copies of the Kathe Kollwitz drawing but one of them looks like the 17th century English poet John Keats and the other one looks like the 19th century poet Arthur Rimbaud.”

When I brought the drawings based on the Kathe Kollwitz piece to class Linda Jo asked me if they represented the same person. “Yes,” I replied they are both copies of the Kathe Kollwitz drawing but one of them looks like the 17th century English poet John Keats and the other one looks like the 19th century poet Arthur Rimbaud.”

A few people in the class laughed supportively and murmured hesitant approval. Linda Jo looked at me seriously and said, “We like your drawings Michael, but there are problems with the proportion of the head and the location of the ears.” She pointed out the areas of concern and reexplained the principles that we had been taught the previous week.

Then she told us that a drawing does not have to look exactly like the person or thing being drawn to be a good drawing and she encouraged us to keep developing our drawing skills.

The skills we were learning, she explained, were intended to enable us to understand the principles of drawing not to produce photographs with a pencil. “There something is going on with you,” she said to me smiling.

To draw well, all of the requisite skills must be integrated and available to the artist simultaneously. One evening Russell brought a book to class entitled “A Whole New Mind” by Daniel Pink. “The ability to draw requires that we learn to think symphonically and assimilate new associations and ideas. To put it musically, you must orchestrate,” she said.

To draw well, all of the requisite skills must be integrated and available to the artist simultaneously. One evening Russell brought a book to class entitled “A Whole New Mind” by Daniel Pink. “The ability to draw requires that we learn to think symphonically and assimilate new associations and ideas. To put it musically, you must orchestrate,” she said.

Pink uses the term “symphony” to describe the capacity to “synthesize rather than analyze; to see relationships between seemingly unrelated fields; to detect broad patterns rather than to deliver specific answers; and to invent something new by combining elements nobody else thought to pair.” Pink maintains that learning to draw is one of the best ways to understand and develop the aptitude of “symphony.”

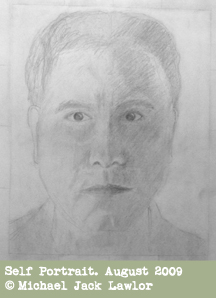

Our last assignment was to draw a self portrait. We worked with an elaborate setup involving a mirror, a viewfinder and a lamp. To make the self portrait we had to incorporate all of the skills learned to date.

After setting eye and chin levels, finding the base of the nose and breaking the width of the eyes into thirds, I began to draw. For the next hour I pulled light with my eraser and searched for values by pressing harder with my pencil. Slowly a likeness began to emerge as I applied the various techniques that Linda Jo had patiently taught us over the summer.

Check out the Los Angeles Acadamy of Figurative Art.

See what’s going on at the Otis College of Art and Design.

Learn more about Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain.

Visit Daniel Pink’s website.

Read about Kathe Kollwitz.

what a terrific piece Michael! We have that book too – Ian uses it himself and we used it with Joe when we were homeschooling him. I like your drawing a lot.

XXL

A very nice write Mike. I found it highly instructive and infomative.

I am seeing negative space in a greater light. And, today, using a few

explained techniques, I attempted to draw a face. It bore some similarites

to the actual photo!Thanks.

Michael, I love this story. Your journey is so familar. I love the progress in your work and I am not surprised by your talent. I know that you work for your accomplishments and it shows here.

I too have used the Betty Edwards book (bummed that I did not suggest it). I had an art project to do and my significant other was an artist; she suggested the book. What a great book. Betty taught at Cal State Longe Beach when I was there in the late ’80s. Her classes would fill so fast that they stopped putting her name on the catalogue.

As always, you inspire me.

Thanks for sharing this,

Captain Gregg