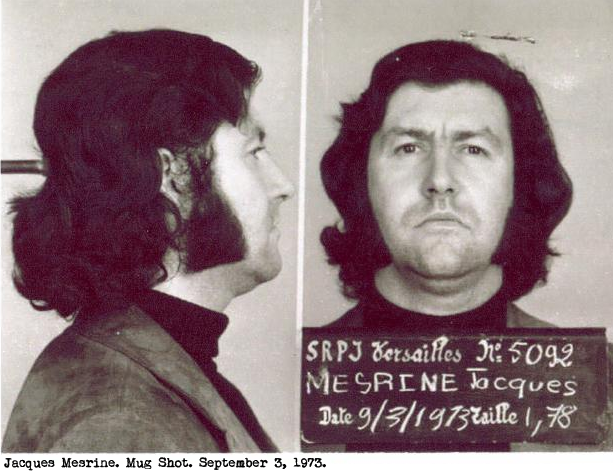

Jacques Mesrine was a French criminal active in Europe and North America during the 1960s and 70s. He was killed by police in the streets of Paris on November 2, 1979.

Mesrine is a legend in the outer arrondissements of French cities, where people romanticize his gangster lifestyle.

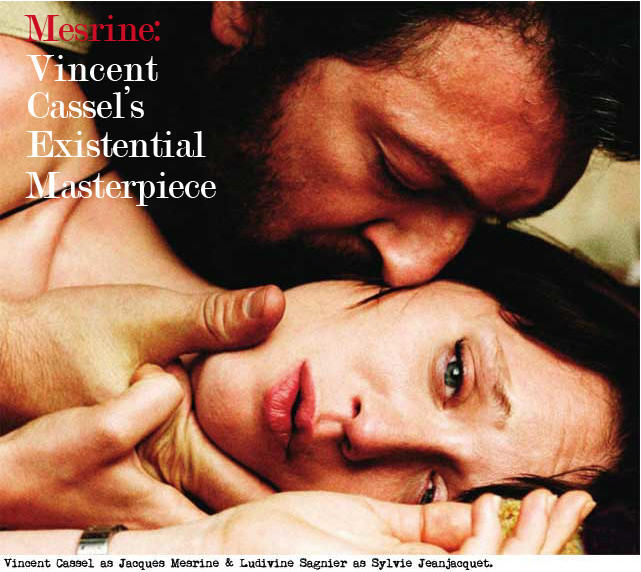

In 2008, a four hour film about Mesrine starring Vincent Cassel appeared in France.

The first part of the film, “Mesrine: Death Instinct”, is based on Mesrine’s autobiography and covers the early years in Algeria, France and Canada. The second part, “Mesrine: Public Enemy Number One”, depicts his life in France during the 1970’s.

“Death Instinct” was released in the United States in August, 2010, followed by “Public Enemy” in September.

On a beautiful summer afternoon in August, I met with Vincent Cassel at the French Consulate in Beverly Hills to talk about the strange allure of this notorious criminal.

![]()

Over a twenty year period Jacques Mesrine executed bank robberies, kidnappings and murders in six countries. He escaped from prison four times, wrote two books, posed as a political revolutionary, and declared armed robbery to be a form of relaxation.

Mesrine’s capacity for rebellion surfaced early. As a boy he was expelled from a prestigious Catholic school in Paris for beating up the headmaster.

He justified his crimes by claiming the French state had wounded his humanity by ordering him as a soldier to kill prisoners after they had been tortured during the Algerian war.

After the war, Mesrine was in perpetual conflict with a political and financial system that he claimed to despise. He took pleasure in mocking the government and the police, encouraging them to shoot first and ask questions later. He planned his crimes with military precision, killing anyone who got in the way.

Vincent Cassel, one of the most interesting French actors in the movies today, deconstructs the mythology of Mesrine to reveal a ruthless, self-centered individual who, by nature, betrayed family and friends.

“He had the violence in him from the start,” said Cassel. “Even though he really tried to find different kinds of justification for his choices in life throughout his career, none of them were right really. I think he was just dreaming of being a gangster, like the movies he was watching on the boulevard in Paris when he was a kid.”

Cassel’s energetic performance reinforces the romantic image of Mesrine as an outlaw while exploring the racism and violence that energized his criminal career.

“There is magic going on with this character. From the start I wanted to keep things clear about what he did. The first director we had in mind wanted to get rid of the racism, the violence against women, but I said there is no point of making a movie about this guy if you take away all of the dirt. The magic that happened in his lifetime is that people still liked him. We had to recreate that magic throughout the movie. I think when you do violent movies today you are closer to reality,” said Cassel.

Cassel portrays Mesrine as a deeply-flawed anti-hero, dedicated to crime and prepared to die as an outlaw. His performance charms and repels. The film is an existential masterpiece.

“He became what he wanted to be and he was prepared to pay the price. If there is one reason why people admire him so much, especially the poor, it is because he was against the system and he was ready to pay the price. I have to say that he was very brave in that sense. He knew exactly what he was doing,” said Cassel.

Mesrine spoke to newspaper and magazine reporters about his crimes, posed for photographers with guns drawn, authored two books, and wrote articles demanding that maximum security prisons be reformed.

He also wrote poetry. A collection of his love poems was published this year, adding another dimension to the mythology.

The poems were written for Martine Malinbaum, his lawyer. Malinbaum, a tireless advocate for the Mesrine family, believes he was illegally assassinated by the police.

“A man who puts himself out so far is often a source of inspiration for those who wouldn’t dare,” said Cassel. “Mesrine surely committed some unforgivable acts at times and he also pulled off some exceptionally daring deeds. It is precisely those contradictions that make for such an exciting character. Some will think he’s despicable and reactionary; some will like the fact that he followed his own path right to the end, shouldered the responsibility, and will identify with him. I find it hard to judge him.”

![]()

Banlieues films emerged as an identifiable genre in French cinema in the 1990’s. Banlieues is the French word for suburb. The films tell the stories of African and Arab immigrants living in the outer arrondisements of large French cities where discrimination, racism and violence are aspects of daily life and social services like health care and education are withheld.

Vincent Cassel’s breakthrough performance was in La Heine (The Hate), a movie about the lives of three unemployed young men in the suburbs. La Heine is a classic of the banlieues genre.

“La Heine that has a lot to do with the suburbs, so I always had this relationship with my fanbase, which is the suburbs. It’s very mixed with a lot of second generation Algerians. They are the biggest fanbase of Mesrine. This guy started his career by killing Arabs. The first man was an Arab and then the second was an Arab. He didn’t have to kill the second one. It was just to prove to himself that he was a real gangster. I really liked the idea of shocking those people by telling them that their hero is not that clean. But funny enough, now that the movie has been out in France for awhile and it’s been on TV and on DVD, people still love him the same way today.”

Cassel grew up in Paris and remembers the day Mesrine was killed by the police.

“He got shot in my neighborhood,” said Cassel. “I’m from the 18th arrondisment, Montmarte. Place Clignancourt, where Mesrine was shot, is actually with walking distance. I was 12 or 13. At the time, they exposed his bloody body on prime time TV at 8 o’clock. ”

Cassel’s father, Jean-Pierre Cassel, was an actor known in France for starring in Philippe de Broca comedies, as well as for his appearance in L’armée des ombres (Army of Shadows), Jean-Pierre Melville’s film about the French resistance. Jean-Pierre Cassel died in 2007.

“I couldn’t do the light bourgeois movies that my father did,” said Cassel. “I needed to find my own identity. I wanted to transform myself and do something else. La Heine was definitely a character very far away from what I am in real life. It was a blessing really, because from the start people didn’t understand who I was. For years people did not know who I was. Now I’m fucked.”

To portray Mesrine in middle age, Cassel, gained forty-five pounds and discovered how the extra weight impacted his movements and voice.

“To play this part, it was always clear that I owed it to myself to gain forty-five pounds. I didn’t realize just how much this changes things. You don’t act the same way when you’re forty-five pounds heavier. The way you move, the way you walk, the way you breathe and even the way you speak changes. Everything is different. Not only are those forty-five pounds visible on the screen, you can hear them in the sound. I put the weight on prior to the shoot and I lost it in nine months over the length of the shoot. We shot backwards because I knew I couldn’t gain a single pound when I was working. The stress on the set always makes me lose weight. Even with the medical supervision, this is the last time I submit my body to that kind of swing in weight.”

![]()

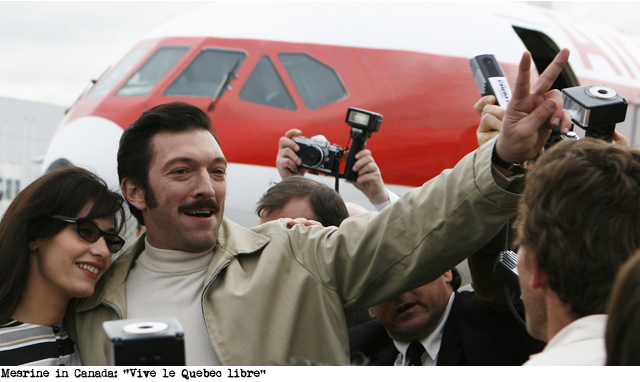

Mesrine emerged as a reality TV star in the Canadian news media.

In 1969, to avoid robbery charges in France, he killed a girlfriend’s pimps and moved from Paris to Quebec.

In Montreal, Mesrine became friends with a member of the FLQ, who he met on a construction site. The men pulled off spectacular crimes together, robbing two banks on the same day – one after another – and hitting another bank twice in three days.

In addition to the robberies, Mesrine kidnapped a wealthy Quebec businessman and negotiated a $200,000 ransom.

The crimes became sensational news items in Canada. To avoid the heat, Mesrine crossed over into the United States where he watched the Apollo launch at Cape Kanaverel and checked into the Waldorf Astoria in New York.

The crimes became sensational news items in Canada. To avoid the heat, Mesrine crossed over into the United States where he watched the Apollo launch at Cape Kanaverel and checked into the Waldorf Astoria in New York.

He was arrested in Arkansas, extradicted to Canada and charged with kidnapping and robbery. The media were waiting for him at the airport in Montreal. When asked by the press for a comment, Mesrine repeated the controversial statement made by French president Charles de Galle during his visit to Montreal in the summer of 1967: “Vive le Quebec libre.” Mesrine discovered how he could use the press to establish himself as public enemy number one.

Mesrine kept the Canadian press busy with drama. He escaped from a holding jail in Percé, Quebec in August, 1969 by sharpening the handle of an aluminum mug and using it as a knife to take keys from a guard.

He was caught and sent to St-Vincent-de-Paul, an escape-proof, maximum security prison in Laval, Quebec.

He escaped from St-Vincent-de-Paul by cutting through three layers of fencing during an exercise period and crawling to freedom. He took five prisoners with him and returned a few days later with a small army to liberate the other prisoners.

Mesrine failed to free the others but he wounded two guards and fled to Venezuela. His reputation as a folk hero grew.

Back in France, Mesrine brutally punished Jacques Tillier, a right-wing reporter who wrote an article that challenged Mesrine’s persona as a political revolutionary.

Mesrine lured Tillier to a cave on the pretext of an interview but instead beat him mercilessly and shot him three times: once in the face for speaking lies, once in the arm for writing lies, and once in the leg, for fun.

He callously photographed the journalist’s ordeal and left him for dead. Against all odds, Tillier survived and now works as newspaper editor on the French island of Reunion in the Indian Ocean.

“Everybody agrees that Mesrine is a terrible person and he’s not respectable, but in a way you like him,” said Cassel.

“When we were shooting the scenes with the journalist or the scene with his wife, I turned to the director and said ‘We might lose the audience. Do you realize that?’ He said, ‘Yeah, but this guy is an extreme right journalist so in a way it’s right.’ ‘Okay, but you agree that we can’t do things like this.’ In the end it worked.”

As Mesrine’s crimes pile up on screen, you have to wonder if there is a market in the U.S. for a four hour movie about a sadistic French criminal.

“American audiences like gangster movies,” said Cassel. “Its part of the culture. Mesrine is very exotic, very French, very Paris. Like Pigalle. The way the characters dress, the way they act. It’s very, very French. Two factors that might seduce an American audience. It’s violent and French.”

“The good thing about it is, if they like the first one, eventually they will pay and go see the second one. So it can be economically interesting. It’s been interesting in France and England and in quite a few countries actually.”

Cassel never loses the audience because he humanizes Mesrine by showing his limitations. We see Mesrine making stupid decisions, misreading people, suffering delusions of grandeur and bickering with girlfriends.

The emotional heart of the film is Mesrine’s relationship with his father. Wearing a disguise, Mesrine sneaks into his dying father’s hospital room and begs forgiveness for what he has done with his life.

“Most of us are dreaming of being free of the system, but we don’t have the opportunity, we don’t have the guts, we don’t have the possibility of doing this. We don’t want to die shot by the policemen in the middle of the street,” said Cassel.

“People want to do what he did, they want to be a rebel, they want to be a gangster, because they think it’s tough, they think it’s cool. But Mesrine didn’t think it was cool. He said, ‘There are no heroes in criminality.’ In a way that’s the best legacy that he left.”

“I think he realized that he really messed up his life. He couldn’t take care of his kids. I’ve met his kids. Honestly, except for the first one, the girl, she’s fine, but the two boys are a mess. They had no father.”

Still photographs courtesy of Music Box Films

Visit the African Market in Paris with Vincent Cassel.