The Two Escobars is a documentary about the rise and fall of narco-soccer in Colombia in the 80’s and 90’s. Drug lords with a deep love of soccer – and the need to launder cash – poured money into the game. Colombian players, who had been obscured by poverty, suddenly emerged on the world stage as winners with an exciting new style of play.

The Two Escobars was made by filmmakers Jeff and Michael Zimbalist as part of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series. The film unfolds at the crossroads of sports, crime and society, mixing archival footage with interviews that show how Colombian athletes, politicians and criminals feel about narco-soccer today.

I called Jeff Zimbalist in New York to talk about the film. He revealed a passionate interest in the developing world and how war torn countries are represented by journalists, filmmakers and artists.

The Two Escobars was screened at the Los Angeles Film Festival on on June 18 and 20, 2010.

![]()

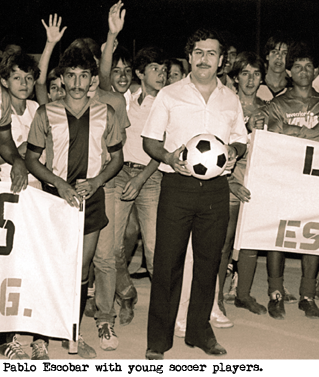

Pablo Escobar, Columbia’s notorious drug lord, bankrolled his countries national soccer team at the height of his power, creating the conditions for coaches and players to transform the sport and the way the world perceived their country.

The mix of drug money and athletic talent produced an explosive soccer team that seemed to appear out of nowhere on the world stage. The Colombian players took creative risks on the field and emerged as World Cup contenders in 1990 and 1994.

“Colombian soccer didn’t exist,” said coach Francisco Maturana, in The Two Escobars. “Then suddenly everyone knew about us. We rose so fast people got suspicious. Two factors converged. One, we had an exceptionally strong team. Two, we had the money to keep our good players. When people saw our situation, people said, but couldn’t prove, ‘Nacional is backed by Pablo Escobar’.”

The Colombian model, however, was not sustainable and the team flamed out at the 1994 Word Cup in California. Behind the scenes, drug lords were betting on games and manipulating the roster. The team played under threats and, back in Medellin, a player’s brother was killed to revenge Colombia’s loss to Romania.

“Drug money, blood money, though it may bring temporary success, inevitably, somewhere down the road, it always ends in tragedy,” said journalist Cesar Mauricio Velasquez, in the film.

Candid interviews with athletes, politicians and criminals from the Pablo Escobar era provide multiple perspectives for the many layers of this complex story.

The filmmakers show that the rise of Pablo Escobar and the success of the Colombian national soccer team were deeply related aspects of conditions in Colombian society.

“When you sit down with people often they would say I don’t want to talk about narco, I’ll talk about sport or I’ll talk about politics but if you so much as mention the word narco, I’m going to get up and walk out of the room,” said Jeff Zimbalist.

“But as soon as you sit down, within 10 minutes of talking about soccer, they’re talking about narco-soccer. That’s because the two are inseperable. You can’t talk about the Chicago Bulls in the 1990’s without mentioning Michael Jordan, just like you can’t talk about the suspiciously rapid rise of soccer in Columbia during the late 80’s without talking about narco.”

![]()

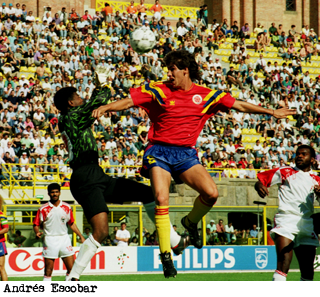

Andrés Escobar, no relation to Pablo, was born on 13 March 1967 in Medellin. Andrés was a professional soccer player employed by the Colombian national team. Fans referred to him as “Football’s Knight” (El Caballero del Futbol).

During a FIFA World Cup match against the United States on June 22, at the Rose Bowl in Pasedena, Andrés deflected a pass from an opposing player into his own goal. Columbia lost the game 2-1 and were eliminated from the tournament in the first round.

Back in Medellin at 3 AM on the morning of July 3, Andrés was shot to death by a gunman in the parking lot of the El Indio nightclub. The killer mocked Andrés as he shot him, shouting “Goal” each time he pulled the trigger, as if he were providing play-by-play commentary during a soccer game.

There has been much speculation that Andrés was assassinated by drug lords who took revenge for the heavy gambling losses that resulted when Andrés scored on his own goal, causing Columbia to lose to the United States in the World Cup.

“In prison, I heard inside information,” said Jhon Vasques in The Two Escobars. “Andrés mistake was talking back to those guys. It had nothing to do with betting. It was a fight, that’s all.” Vasques, aka Popeye, was Pablo Escobar’s right hand man in the Medellin cartel.

![]()

Pablo Escobar was born in Medellin, in 1949. He grew up during La Violencia (The Violence), a period of guerilla warfare that tore apart the Columbia countryside. Millions of people were displaced from their homes during the conflict, which was characterized by conspiracy theories and murder. The judicial system broke down during La Violencia and journalists were silenced.

Pablo studied political science at university but never graduated.

Early in his criminal career Pablo stole cars, ran confidence games, recycled gravestones and orchestrated kidnappings. He entered the drug trade in 1975 and within 10 years, emerged as the leader of the Medellin cartel, controlling 80% of the global cocaine market.

In it’s 1989 mashup of capitalism and crime, Forbes magazine listed Pablo Escobar as the seventh richest man in the world. Pablo’s ROI was believed to be 200%. He could earn 50 million dollars a day.

Figuring out what do with the cash was a problem. Storage issues caused him to write off 10 percent of his earnings due to mould and rodents. He seeded piles of money with coffee beans to offset the stench produced by mounds of dormant paper.

Pablo enforced his business model in Columbia with a reign of terror. He bribed police and politicians with an offer that couldn’t be refused, the notorious “plata o plomo” (silver or lead). People either accepted the bribe or they were shot.

He was responsible for the assassination of political candidates and judges. He ordered the bombing of Avianca Flight 203, killing hundreds of passengers in a failed attempt to assassinate a political rival who was not on the plane. Several American citizens were killed in the attack, making Pablo public enemy number one in the U.S..

The New York Times reported that the Medellin cartel were behind the bombing of the Administrative Department of Security (DAS) headquarters in Bogotá. The blast killed 52 people, injured 1000, levelled city blocks and destroyed hundreds of commercial properties. The cartel’s target, DAS director Miguel Maza Márquez, was not injured in the blast.

Pablo’s appearance in the Forbes top ten billionaire list reflected an insatiable demand for cocaine in United States. George Jung, aka Boston George, worked closely with Pablo to create a market for the drug in the U.S. by developing smuggling routes and distribution networks

Boston George had a working knowledge of the laws of supply and demand. He wanted to contain the risk of getting busted by keeping supply low and prices high. The Medellin cartel had other plans.

According to Boston George, the Medellin cartel began to see cocaine as a weapon that could be used to undermine American society.

“Carlos [Lehder] had the concept where he wanted to flood the country with cocaine and destroy the political and moral structure of the United States. As he stated, cocaine was the atomic bomb and he was going to drop it on America,” said Boston George in a Frontline interview in 2000.

Crack had a devastating effect on American cities. Crime rates soared as people scrambled to feed cocaine addictions. The huge sums of cash involved in cocaine trafficking made drug deals violent. Drug traffickers understood that marijuana deals were conducted with a handshake, cocaine deals with a gun.

Flooding the U.S. with cocaine proved to be an unwise business decision. Pablo lost control of the operation as the scope expanded. He also incurred the wrath of the U.S. government.

“Pablo was still known as the head of the cartel but I think in that sense he really became a figurehead. It all grew beyond his comprehension,” said Boston George in 2000.

By the early 90’s Pablo found himself at war with the United States. The American military worked with the Colombian police and a paramilitary organization to destroy his infrastructure, leaving him vulnerable and alone.

By the early 90’s Pablo found himself at war with the United States. The American military worked with the Colombian police and a paramilitary organization to destroy his infrastructure, leaving him vulnerable and alone.

Pablo Escobar was killed in Medellin on December 2, 1993 by forces employed to take him out.

Yet, Pablo was a folk hero to many poor people in Colombia. He built houses, schools, churches and health clinics in areas of the country neglected by the government. He built homes for 700 families living in misery on a municipal dump. The community is called Barrio Pablo Escobar.

He built soccer fields in communities that did not have recreational facilities, giving poor people a chance to enjoy sport and forget their troubles. Many of the players on the Colombian team grew up playing soccer on fields built by Pablo Escobar.

“The deaths of Pablo Escobar and Andrés Escobar mark the end of the glory years of Colombian soccer,” said Jaime Gaviria, Pablo’s cousin, in the film.

![]()

Colombian soccer players redefined the image of Columbia in the world by expressing themselves on the field with discipline, creativity and grace. Francisco Maturana, Columbia’s coach, encouraged the players to be creative on the field.

Maturana emerges as the philosopher-poet of Colombian soccer in the film. He speaks of soccer in the context of Columbia’s national identity and muses that the creativity of his players was an expression of the spirit of the Colombian people.

Maturana emerges as the philosopher-poet of Colombian soccer in the film. He speaks of soccer in the context of Columbia’s national identity and muses that the creativity of his players was an expression of the spirit of the Colombian people.

“When I was a player we always played from a place of fear,” said Maturana in the film. “As a coach, I wanted my players to express themselves and let’s see what happens. When fans saw that personality they said, ‘Yes that’s who we are. That’s our team. Our identity. They embraced us and infused us with the joy that is the heart of our people. We manifested their dreams, ignited their passion. No longer were we Medellin or Cali. No. We were Columbia.”

Colombian soccer restored the self-esteem of the nation by showing that there was more to their country than drugs and crime.

“Francisco Maturana was willing to discuss with his players the society they were living in at the time just as he was willing to discuss it with us on camera,” said Jeff Zimbalist.

“He knew that it was a part of their experience and he knew that it needed to be embraced, that it couldn’t be ignored, that it couldn’t be separated, it had to be an integrated part of the experience of coaching and rallying and unifying his team. He had some vision and insight into using one’s emotion, using one’s pain and one’s fear as an asset, as an opportunity. He had an incredible group of players at the time and he had some money to work with. It was a remarkable, unexpected confluence of all these factors that led to a squad that just played from heart and memory.”

“He knew that it was a part of their experience and he knew that it needed to be embraced, that it couldn’t be ignored, that it couldn’t be separated, it had to be an integrated part of the experience of coaching and rallying and unifying his team. He had some vision and insight into using one’s emotion, using one’s pain and one’s fear as an asset, as an opportunity. He had an incredible group of players at the time and he had some money to work with. It was a remarkable, unexpected confluence of all these factors that led to a squad that just played from heart and memory.”

The scorpion kick, invented by Columbia’s goalkeeper Rene Higuita, symbolized the inventiveness of the Colombian team. To realize a scorpion kick a goalkeeper must leap forward, pull his legs back over his head and kick the ball away with his heels.

“The scorpion kick is one of the more famous and daring moves in soccer history and I think that reflects one of the most daring, outlandish, creative and imaginative teams in the history of soccer,” said Jeff Zimbalist.

![]()

The Two Escobars begins and ends with the story of Andres Escobar deflecting the ball into his own goal. The filmmakers frame the story of Colombian society in the late 20th century with that unfortunate mistake.

“When you’re dealt so many characters, so many protagonists, so many different layers of story, like in this case, you have sports, society, politics, then you have the international image of a country, you know the United States involvement, all of that, it’s real important to use structure and to know structure,” said Jeff Zimbalist. “We apply the rules and logic of screenplay structure to documentary story telling.”

One of the themes in the film is the danger of building cultural forms on corrupt foundations. The phenomenon of narco-soccer blazes triumphantly across the screen before crashing and burning in the white heat of it’s own intensity.

“It was important to us that the film also speak to a portrait of Colombia as a place that is coming together successfully, that is transforming it’s situation, that is full of people who, like Andreas Escobar, have a vision for the country that is not based on illicit money, who understand that if you build a structure on a faulty foundation that it’s destined to collapse,” said Jeff Zimbalist.

“Shortcuts like drug money in the sport of soccer is a microcosm of what happens when you take shortcuts at the societal level.”

Archival footage is presented in standard definition with a chartreuse color correction that lends historical imagery a slightly lurid tone. Interviews with athletes, politicians and criminals are presented in high definition, which creates a sense of clarity as people reflect on Columbia’s past.

The filmmaker’s worked with composer Ion Furjanic to develop a blend of hip hop beats and middle eastern rhythms that propel the narrative.

“It was important to us from the beginning to make sure that we didn’t just extend a negative stereotype of Columbia,” said Jeff Zimbalist.

“Most, if not all, mainstream media portraits of Columbia that we have access to in the United States are of a place falling apart, a hot bed of violence, corruption and drugs, and while I’m not gonna deny that there is a lot of that in existence even today, and there was far more so back in the late 80’s early 90’s that we are dealing with in the film, Columbia is overwhelmingly a country full of peace loving and hardworking people.”

“Our experience, my brother and I, living and working in Columbia and living and working in the developing world in general is not one of fear and violence. It’s actually a love affair with these places. We fell in love with Columbia working there.”

Michael, You really make me want to view this movie. I knew some of the content and not all. I think this topic is so vast that one documentry would have to be 4 hours long at least. I would like to see if there are any references to the US Goverment involvement with Ollie North bringing in plane loads of cocaine to fund his private war.

Thanks for clear, concise writting. Nice Job, G

[…] Capitalism has been a big part of the World Cup with the funding as well (the name of it being Narco-Soccer, more in COLOMBIA: The Rise and Fall of Narco-Soccer | Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) and […]