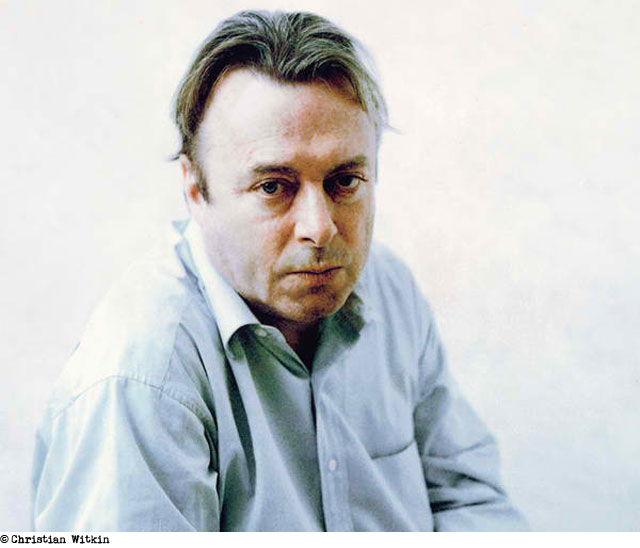

Christopher Hitchens, who died of cancer in Houston on December 15, 2011, spoke at public events in Los Angeles many times. I was fortunate to catch a few of his appearances and see him in action.

Five days before the United States invaded Iraq in March 2003, Hitchens spoke at the Wiltern Theatre in Koreatown. He was debating the upcoming war with Robert Scheer, Michael Ignatieff and Mark Tanner. The event was billed as “American Power & The Crisis Over Iraq.” The house was packed.

At one point during the debate Hitchens nailed Robert Scheer for misquoting Karl Marx.

“Christopher always talks about religion as being the, I guess what, the … what was the thing Marx said? Opium of the people …” said Scheer.

“No, he didn’t. No, he didn’t,” said Hitchens immediately.

Ten or fifteen minutes later, when it was his time to speak, Hitchens corrected Scheer.

“What Marx said about religion, by the way, was that it was the heart of the heartless world, the sigh of the oppressed creature, the spirit of the spiritless situation, an opiate for the people, and that criticism had plucked the flowers from the chain not so that men could wear the chain without consolation, but so that they could break the chain and cull the living flower.”

The poetry of Karl Marx is rarely heard in the concert halls of America. Like a lustre from the page, Hitchens’ brief recitation of Marx expanded the edge of the debate and set him apart from the others who now seemed to fumble with notes and rely on disfluencies to transition from thought to thought. Hitchens, more than the others and whether you agreed with him or not, had the ability to make you wonder what he was going say next.

He chastised the audience for applauding his fellow panelists and he infantilized Michael Ignatieff by interrupting him to point out that he had confused “moral perfectionism” with “moral relativism.”

At UCLA’s Royce Hall in April, 2004 during a debate billed as “U.S. And Iraq One Year Later: Right to Get In? Wrong to Get Out?” Hitchens, who supported the war, responded to the hisses and jeers of the audience by telling everyone to “fuck off.” The room fell silent.

From the stage he was charming but slightly vicious. He could evoke the street as well as the academy and he added a touch of menace to an event.

Hitchens’ support of the war may have been rooted in the anti-totalitarian principles of his youth but he was chilling as a cheerleader for the unwholesome characters who he believed would set his dream of a democratic Iraq in motion. His war cry was tempered by the charm of his trademark irony and obscenity.

Hitchens knew how to seduce a room. The hostility he excited in his detractors, he once told a reporter, “washes off me like jizz off a porn star’s face.”

In June, 2007 Hitchens spoke at the Los Angeles Public Library to promote “God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything.” He drank what appeared to be scotch from a clear glass and slurred his speech throughout the evening.

At one point he lamented the loss of a golden age.

“We can recover the lost connection – the one that monotheism severed – between Athens and Jerusalem, and we could get back a world where philosophy was valued, the beauty of science considered worth studying, worth revering even, where literature would be the key to the study of ethics and morality. If you wanted the transcendent, you’d have love and sex and music, and you wouldn’t need supernatural permission. I miss it terribly. I feel as if something was torn away from me before I was born.”

At the end of that June evening Hitchens got into a dispute with an audience member who felt deeply insulted that Hitchens had refused to take his question about the attacks on September 11, 2001.

Hitchens would only tell the man that he was a “witless fool.”

Rattled by the insult, the man stormed the edge of the stage to confront Hitchens. As the two men shouted at one another library security arrived to remove the audience member, but Hitchens intervened. He told security that although the guy was a “witless fool” he did not want to see him forcibly removed from the theatre.

Security, not about to take orders from Hitchens, told the man to leave with them. Hitchens took the arm of his antagonist, pulled him up onto the stage, offered him a cigarette and escorted him toward the backstage exit.

“You are a witless fool,” he said. “But I do not want them to arrest you.”

Christopher Hitchens: ‘the consummate writer, the brilliant friend’ by Ian MacEwen.

Christopher Hitchens: Reason in Revolt by Robert Scheer

Christopher Hitchens Is Hailed by Stephen Fry as a Man of Style and Wit

Hitchens at the LA Public Library

Hitchens at the Wiltern – American Power & The Crisis Over Iraq (transcript)

Michael, I think this is nicely written. I like the concise way you summed up Hitchens. I remember that you introduced me to him years ago with one of his books. You took me to one of the debates you mentioned. I was opended to a new voice. Thank you so much for that.

I think he was a great mind who had great courage as well as arogance.

He is missed; his influence will continue although with less strength, I think.

Good article, but Hitch was incorrect, Iggy meant perfectionism.